HTTP/3 is here, and it’s a big deal for web performance. See just how much faster it makes websites!

Wait, wait, wait, what happened to HTTP/2? Wasn’t that all the rage only a few short years ago? It sure was, but there were some problems. To address them, there’s a new version of the venerable protocol working its way through the standards track.

Ok, but does HTTP/3 actually make things faster? It sure does, and we’ve got the benchmarks to prove it.

Quick Preview

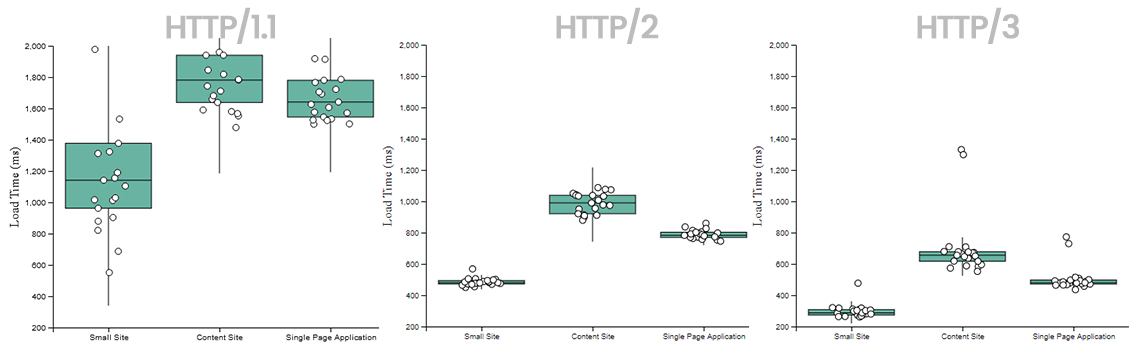

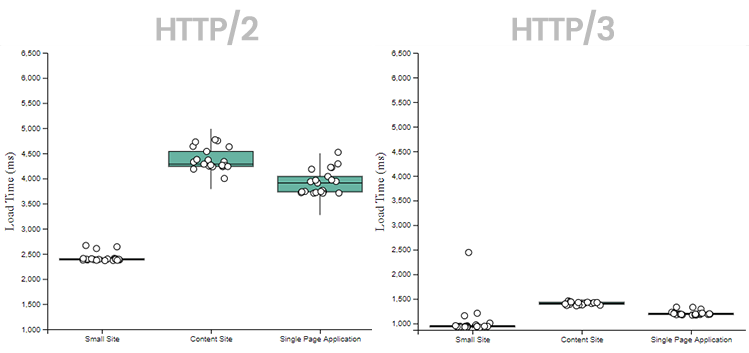

Before we get too deep in the details, let’s look at a quick preview of the benchmark results. In the charts below the same browser was used to request the same site, over the same network, varying only the HTTP protocol in-use. Each site was retrieved 20 times and the response time measured via the performance API. (More details on benchmark methodology later)

You can clearly see the performance improvement as each new version of the HTTP protocol is used:

And the changes become even more pronounced when requesting resources over larger geographic distances and less reliable networks.

But before we can get fully in to all the HTTP/3 benchmark minutiae, a little context is required.

A Brief History of HTTP

The first official version of HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol 1.0) was finalized in 1996. There were some practical issues and parts of the standard that needed updating, so HTTP/1.1 was released a year later in 1997. Per the authors:

However, HTTP/1.0 does not sufficiently take into consideration the effects of hierarchical proxies, caching, the need for persistent connections, and virtual hosts. In addition, the proliferation of incompletely-implemented applications calling themselves “HTTP/1.0” has necessitated a protocol version change in order for two communicating applications to determine each other’s true capabilities.

It would be 18 more years before a new version of HTTP was released. In 2015, and with much fanfare, RFC 7540 would standardize HTTP/2 as the next major version of the protocol.

One File at a Time

If a web page requires 10 javascript files, the web browser needs to retrieve those 10 files before the page can finish loading. In HTTP/1.1-land, the web browser can only download a single file at a time over a TCP connection with the server. This means the files are downloaded sequentially, and any delay in one file would block everything else behind it. This is called Head-of-line Blocking and it’s not good for performance.

To work around this, browsers can open multiple TCP connections to the server to parallelize the data retrieval. But this approach is resource intensive. Each new TCP connection requires client and server resources, and when you add TLS in the mix there’s plenty of SSL negotiation happening too. A better way was needed.

Multiplexing with HTTP/2

HTTP/2’s big selling point was multiplexing. It fixed application level head-of-line blocking issues by switching to a binary over-the-wire format that allowed multiplexed file downloads. That is, a client could request all 10 files at once and start downloading them all in parallel over a single TCP connection.

Unfortunately HTTP/2 still suffers from a head-of-line blocking issue, just one layer lower. TCP itself becomes the weak link in the chain. Any data stream that loses a packet must wait until that packet is retransmitted to continue.

However, because the parallel nature of HTTP/2’s multiplexing is not visible to TCP’s loss recovery mechanisms, a lost or reordered packet causes all active transactions to experience a stall regardless of whether that transaction was directly impacted by the lost packet.

In fact, in high packet loss environments, HTTP/1.1 performs better because of the multiple parallel TCP connections the browser opens!

True Multiplexing with HTTP/3 and QUIC

Enter HTTP/3. The major difference between HTTP/2 and HTTP/3 is which transport protocol they use. Instead of TCP, HTTP/3 uses a new protocol called QUIC. QUIC is a general purpose transport protocol meant to address the head-of-line blocking issues HTTP/2 has with TCP. It allows you to create a series of stateful streams (similar to TCP) over UDP.

The QUIC transport protocol incorporates stream multiplexing and per-stream flow control, similar to that provided by the HTTP/2 framing layer. By providing reliability at the stream level and congestion control across the entire connection, QUIC has the capability to improve the performance of HTTP compared to a TCP mapping

And improve the performance of HTTP it does! Jump to the results if you don’t care about how the test was conducted

Benchmarking HTTP/3

To see just what sort of performance difference HTTP/3 makes, a benchmarking test setup was needed.

The HTML

In order to more closely approximate actual usage, the test setup consisted of three scenarios - a small site, a content-heavy site (lots of images and some JS), and a single page application (heavy on the JS). I looked at several real-world sites and averaged the number of images and JS files for each, then coded up some demo sites that matched those resource counts (and sizes).

- Small Site

- 10 JS files from 2kb to 100kb

- 10 images from 1kb to 50kb

- Total payload size 600kb, 20 blocking resources total

- Content Site

- 50 JS files from 2kb to 1mb

- 55 images ranging in size from 1kb to 1mb.

- Total payload size 10MB, 105 resources total (look at cnn.com sometime in dev tools and you’ll see why this is so big)

- Single Page Application

- 85 JS files from 2kb to 1mb

- 30 images ranging in size from 1kb to 50kb.

- Total payload size 15MB, 115 resources total (look at JIRA sometime in dev tools)

The Server

Caddy was used to serve all assets and HTML.

- All responses were served with

Cache-Control: "no-store"to ensure the browser would re-download every time. - TLS 1.2 was used for HTTP/1.1 and HTTP/2

- TLS 1.3 was used for HTTP/3.

- 0-RTT was enabled for all HTTP/3 connections

The Locations

The tests were conducted from my computer in Minnesota, to three separate datacenters hosted by Digital Ocean:

- New York, USA

- London, England

- Bangalore, India

The Client

I automated the browser to request the same page 20 times in a row, waiting 3 seconds after page load to begin the next request. The internet connection is rated at 200mbps. No other applications were running on the computer at the time of data capture.

So How Fast Is HTTP/3?

New York, USA

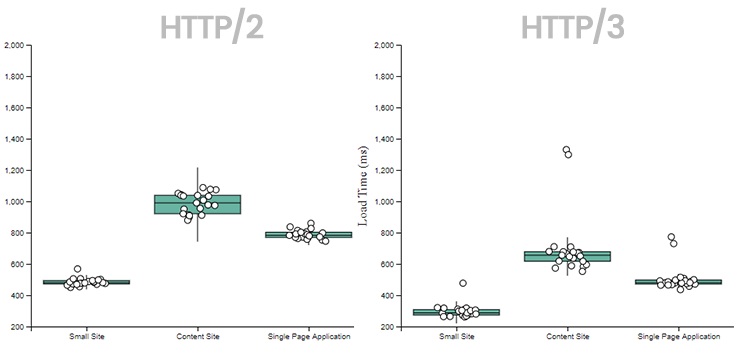

Here’s the response times of HTTP/2 vs. HTTP/3 when requesting the three different sites from the NY datacenter:

HTTP/3 is:

- 200ms faster for the Small Site

- 325ms faster for the Content Site

- 300ms faster for the Single Page Application

The distance from Minnesota to New York is 1,000 miles, which is pretty small by networking standards. It’s significant that even at a relatively short distance HTTP/3 was able to improve performance this much.

London, England

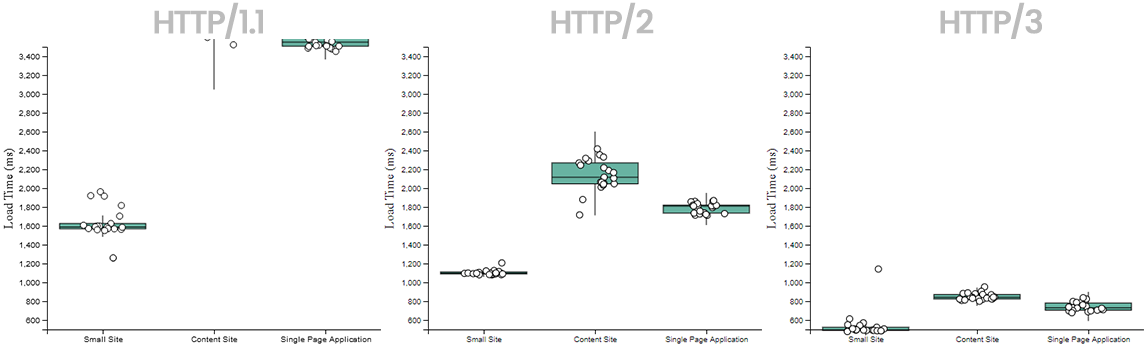

I’ve included the HTTP/1.1 benchmarking run for London in the results as well. In order to show just how much faster HTTP/2 and HTTP/3 are, I’ve kept the graphs to the same scale. You can see that for the Content Site, the timings are so slow that they don’t even fit entirely on the graph!

As you can see, the speed increase is even more pronounced when greater distances over the network are in play. HTTP/3 is:

- 600ms faster for the Small Site (3x the speedup compared with New York)

- 1200ms faster for the Content Site (over 3.5x the speedup compared with New York)

- 1000ms faster for the Single Page Application (over 3x the speedup compared with New York)

Bangalore, India

The performance improvement with HTTP/3 is extremely pronounced when loading pages from the server in India. I didn’t even run an HTTP/1.1 test because it was so slow. Here are the results of HTTP/2 vs. HTTP/3:

HTTP/3 continues to pull ahead when larger geographies and more network hops are involved. What’s perhaps more striking is just how tightly grouped the response times are for HTTP/3. QUIC is having a big impact when packets are traveling thousands of miles.

In every case HTTP/3 was faster than its predecessor!

Why is HTTP/3 so Much Faster?

Real Multiplexing

The true multiplexed nature of HTTP/3 means that there is no Head-of-line blocking happening anywhere on the stack. When requesting resources from further away, geographically, there is a much higher chance of packet loss and the need for TCP to re-transmit those packets.

0-RTT Is a Game Changer

Additionally, HTTP/3 supports O-RTT QUIC connections, which lowers the number of round trips required to establish a secure TLS connection with the server.

The 0-RTT feature in QUIC allows a client to send application data before the handshake is complete. This is made possible by reusing negotiated parameters from a previous connection. To enable this, 0-RTT depends on the client remembering critical parameters and providing the server with a TLS session ticket that allows the server to recover the same information.

However, 0-RTT should not be blindly enabled. There are some possible security concerns depending on your threat model.

The security properties for 0-RTT data are weaker than those for other kinds of TLS data. Specifically:

- This data is not forward secret, as it is encrypted solely under keys derived using the offered PSK.

- There are no guarantees of non-replay between connections.

Can I Use HTTP/3 Today?

Maybe! While the protocol is currently in Internet-Draft status, there are plenty of existing implementations.

I specifically chose Caddy for these benchmarks because HTTP/3 can be enabled with a simple config value in the Caddyfile

NGINX also has experimental support and is working towards an official HTTP/3 release in the near future.

The big tech players like Google and Facebook are serving their traffic over HTTP/3 already. Google.com is entirely served over HTTP/3 for modern browsers.

For those folks stuck in the Windows ecosystem, supposedly Windows Server 2022 will support HTTP/3, with some rather esoteric steps required to enable it.

Conclusion

HTTP/3 can make a big difference in how users experience your site. In general, the more resources your site requires, the bigger the performance improvement you’ll see with HTTP/3 and QUIC. As the standard continues to inch closer to finalization, it may be time to start looking at enabling it for your sites.

Was this article helpful?

That’s Great!

Thank you for your feedback

Sorry! We couldn't be helpful

Thank you for your feedback

Feedback sent

We appreciate your effort and will try to fix the article